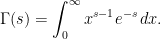

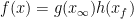

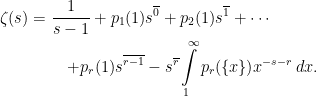

For these initial posts of this blog, I will look at one of the most fascinating objects in mathematics, the Riemann zeta function. This is defined by the infinite sum

|

(1) |

which can be shown to be uniformly convergent for all  with

with  . It was Bernhard Riemann who showed that it can be analytically continued to the entire complex plane with a single pole at

. It was Bernhard Riemann who showed that it can be analytically continued to the entire complex plane with a single pole at  , derived a functional equation, and showed how its zeros are closely linked to the distribution of the prime numbers. Riemann’s seminal 1859 paper is still an excellent introduction to this subject, an English translation of which (On the Number of Prime Numbers less than a Given Quantity) can be found on the Clay Mathematics Institute website, who included the conjecture that the `non-trivial’ zeros all lie on the line

, derived a functional equation, and showed how its zeros are closely linked to the distribution of the prime numbers. Riemann’s seminal 1859 paper is still an excellent introduction to this subject, an English translation of which (On the Number of Prime Numbers less than a Given Quantity) can be found on the Clay Mathematics Institute website, who included the conjecture that the `non-trivial’ zeros all lie on the line  among their million dollar millenium problems.

among their million dollar millenium problems.

In this post I will give a brief introduction to the zeta function and look at its functional equation. In particular, the functional equation can be generalized and reinterpreted as an identity of Mellin transforms, which links the additive Fourier transform on  with the multiplicative Mellin transform on the nonzero reals

with the multiplicative Mellin transform on the nonzero reals  . The aim is to the prove the generalized functional equation and some properties of the zeta function, working from first principles, and discuss at a high level how this relates to the ideas in Tate’s thesis. Some standard complex analysis and Fourier transform theory will be used, but no prior understanding of the Riemann zeta function is assumed.

. The aim is to the prove the generalized functional equation and some properties of the zeta function, working from first principles, and discuss at a high level how this relates to the ideas in Tate’s thesis. Some standard complex analysis and Fourier transform theory will be used, but no prior understanding of the Riemann zeta function is assumed.

The zeta function has a long history, going back to the Basel problem which was posed by Pietro Mengoli in 1644. This asked for the exact value of the sum of the reciprocals of the square numbers or, equivalently, the value of  . This was eventually solved by Leonard Euler in 1734 who discovered the famous identity

. This was eventually solved by Leonard Euler in 1734 who discovered the famous identity

Euler found the values of  at all positive even numbers, although I will not be concerned with this here. More pertinent to the current discussion is the product expression also found by Euler,

at all positive even numbers, although I will not be concerned with this here. More pertinent to the current discussion is the product expression also found by Euler,

|

(2) |

The product is taken over all prime numbers  , and converges on

, and converges on  . Proving (2) is straightforward. The formula for summing a geometric series gives

. Proving (2) is straightforward. The formula for summing a geometric series gives

Substituting this into (2) and expanding the product gives an infinite sum over terms of the form

for  , primes

, primes  , and integers

, and integers  . Using the fact that every positive integer has a unique expression as a product of powers of distinct primes, we see that the Euler product expands as a sum of terms of the form

. Using the fact that every positive integer has a unique expression as a product of powers of distinct primes, we see that the Euler product expands as a sum of terms of the form  as

as  ranges over the positive integers. This is just the right hand side of (1) and shows that the Euler product converges and is equal to

ranges over the positive integers. This is just the right hand side of (1) and shows that the Euler product converges and is equal to  whenever the sum (1) is absolutely convergent.

whenever the sum (1) is absolutely convergent.

The Euler product provides a link between the zeta function and the prime numbers, with far-reaching consequences. For example, the prime number theorem describing the asymptotic distribution of the prime numbers was originally proved using the Euler product, and the strongest known error terms available for this theorem still rely on the link between the prime numbers and the zeta function given by (2). Euler used the fact that (1) diverges at  to argue that (2) also diverges at

to argue that (2) also diverges at  . From this, it is immediately deduced that there are infinitely many primes and, more specifically, the reciprocals of the primes sum to infinity.

. From this, it is immediately deduced that there are infinitely many primes and, more specifically, the reciprocals of the primes sum to infinity.

The Euler product can also be expressed in terms of the logarithm of the zeta function. Using the Taylor series expansion of  , we obtain

, we obtain

|

(3) |

As the terms on the right hand side are bounded by  as

as  runs through the subset of the natural numbers consisting of prime powers, it will be absolutely convergent whenever (1) is. In particular, (3) converges on the half-plane

runs through the subset of the natural numbers consisting of prime powers, it will be absolutely convergent whenever (1) is. In particular, (3) converges on the half-plane  . Although the complex logarithm is generally only defined up to integer multiples of

. Although the complex logarithm is generally only defined up to integer multiples of  , (3) gives the unique continuous version of

, (3) gives the unique continuous version of  over

over  which takes real values on the real line.

which takes real values on the real line.

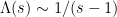

We will first look at the zeta functional equation as described by Riemann. This involves the gamma function defined on  by the absolutely convergent integral

by the absolutely convergent integral

|

(4) |

This is easily evaluated at  to get

to get  , and an integration by parts gives the functional equation of

, and an integration by parts gives the functional equation of  ,

,

This can be used to evaluate the gamma function at the positive integers,  . Also, by expressing

. Also, by expressing  in terms of

in terms of  , it allows us to extend

, it allows us to extend  to a meromorphic function on

to a meromorphic function on  with a single simple pole at

with a single simple pole at  . Repeatedly applying this idea extends

. Repeatedly applying this idea extends  as a meromorphic function on the entire complex plane with a simple pole at each non-positive integer. Furthermore, it is known that

as a meromorphic function on the entire complex plane with a simple pole at each non-positive integer. Furthermore, it is known that  is non-zero everywhere on

is non-zero everywhere on  .

.

The functional equation can now be stated as follows.

Theorem 1 (Riemann) The function  defined by (1) uniquely extends to a meromorphic function on

defined by (1) uniquely extends to a meromorphic function on  with a single simple pole at

with a single simple pole at  of residue

of residue  . Setting

. Setting

|

(5) |

this satisfies the identity

|

(6) |

Riemann actually gave two independent proofs of this, the first using contour integration and the second using an identity of Jacobi. Many alternative proofs have been discovered since, with Titchmarsh listing seven (The Theory of the Riemann Zeta Function, 1986, second edition). I will not replicate these here, but will show an alternative formulation as an identity of Mellin transforms, from which Riemann’s functional equation (6) follows as a special case.

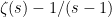

As an example of the use of the functional equation to derive properties of the zeta function on the left half-plane  , we evaluate

, we evaluate  . Using the special value

. Using the special value  and the fact that

and the fact that  has a pole of residue

has a pole of residue  at

at  , we see that

, we see that  as

as  approaches

approaches  . Similarly, using the fact that the gamma function has a pole of residue

. Similarly, using the fact that the gamma function has a pole of residue  at

at  , we see that

, we see that  as

as  approaches

approaches  . Putting these limits into the functional equation gives

. Putting these limits into the functional equation gives

Similarly, the functional equation expresses the values of  at negative odd integers in terms of its values at positive even integers. For example, taking

at negative odd integers in terms of its values at positive even integers. For example, taking  ,

,

Plugging in the values  ,

,  and Euler’s value of

and Euler’s value of  ,

,

Via a process known as zeta function regularization, these special values of  are sometimes written as the famous, but rather confusing, expressions

are sometimes written as the famous, but rather confusing, expressions

Next, using standard properties of the gamma function, theorem 1 can be used to investigate the zeros of the zeta function. The Euler product implies that  has no zeros on

has no zeros on  , as I will show below, and it is well known that the gamma function has no zeros at all. So,

, as I will show below, and it is well known that the gamma function has no zeros at all. So,  has no zeros or poles anywhere on

has no zeros or poles anywhere on  , and the functional equation extends this statement to

, and the functional equation extends this statement to  . It follows that, on

. It follows that, on  , the zeros of the zeta function must cancel with the poles of

, the zeros of the zeta function must cancel with the poles of  , which are at the negative even integers.

, which are at the negative even integers.

On the strip  , the precise location of the zeros of

, the precise location of the zeros of  are not known. However, as

are not known. However, as  has no poles or zeros on this domain (other than at

has no poles or zeros on this domain (other than at  ), they must coincide with the zeros of

), they must coincide with the zeros of  . From the definition (1) of the zeta function, it satisfies

. From the definition (1) of the zeta function, it satisfies  (using a bar to denote complex conjugation). So, its zeros are preserved by reflection

(using a bar to denote complex conjugation). So, its zeros are preserved by reflection  about the real line. Also, by the functional equation, they are preserved by the map

about the real line. Also, by the functional equation, they are preserved by the map  in the aforementioned strip. We have arrived at the following.

in the aforementioned strip. We have arrived at the following.

Lemma 2 The function  has zeros at the (strictly) negative even integers. The only remaining zeros lie in the vertical strip

has zeros at the (strictly) negative even integers. The only remaining zeros lie in the vertical strip  and are preserved by the maps

and are preserved by the maps

|

(7) |

The zeros at the negative even integers are called the trivial zeros of  , with the remaining ones referred to as the non-trivial zeros. The domain

, with the remaining ones referred to as the non-trivial zeros. The domain  is known as the critical strip. So, the non-trivial zeros of the Riemann zeta function are precisely those lying in the critical strip, and are the same as the zeros of the function

is known as the critical strip. So, the non-trivial zeros of the Riemann zeta function are precisely those lying in the critical strip, and are the same as the zeros of the function  defined by (5). The vertical line

defined by (5). The vertical line  lying along the center of the critical strip is called the critical line. Then, (7) says that the non-trivial Riemann zeta zeros are symmetric under reflection about both the real line and the critical line. The Riemann hypothesis, as originally conjectured by Riemann in his 1859 paper, states that the non-trivial zeros all lie on the critical line. This, however, remains unknown and is one of the great open problems of mathematics.

lying along the center of the critical strip is called the critical line. Then, (7) says that the non-trivial Riemann zeta zeros are symmetric under reflection about both the real line and the critical line. The Riemann hypothesis, as originally conjectured by Riemann in his 1859 paper, states that the non-trivial zeros all lie on the critical line. This, however, remains unknown and is one of the great open problems of mathematics.

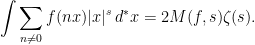

We will now move on to the alternative interpretation of the functional equation relating additive Fourier transforms with multiplicative transforms. We will use the following convention for the Fourier transform of a function  ,

,

For this to make sense, it should at least be required that  is integrable. I will restrict to the particularly nice class of Schwartz functions. These are the infinitely differentiable functions from

is integrable. I will restrict to the particularly nice class of Schwartz functions. These are the infinitely differentiable functions from  to

to  which vanish faster than polynomially at infinity, along with their derivatives to all orders. That is,

which vanish faster than polynomially at infinity, along with their derivatives to all orders. That is,  as

as  , for all integers

, for all integers  . Denote the space of Schwartz functions by

. Denote the space of Schwartz functions by  . Schwartz functions are integrable and it is known that their Fourier transforms are again in

. Schwartz functions are integrable and it is known that their Fourier transforms are again in  . Then, for any

. Then, for any  , its Fourier transform is inverted by

, its Fourier transform is inverted by

I’ll explain now why the Fourier transform (8) is an additive transform of  . For each fixed

. For each fixed  , the map

, the map  is a continuous homomorphism from the additive group of real numbers to the multiplicative group of nonzero complex numbers

is a continuous homomorphism from the additive group of real numbers to the multiplicative group of nonzero complex numbers  ,

,

So,  is a character of the reals under addition. Furthermore, integration is invariant under additive translation,

is a character of the reals under addition. Furthermore, integration is invariant under additive translation,

That is, the standard (Riemann or Lesbesgue) integral is the Haar measure of the additive group of reals, and the Fourier transform (8) is the integral of  against additive characters with respect to the additive Haar measure.

against additive characters with respect to the additive Haar measure.

The Mellin transform of  is

is

which is defined for any  for which the integral is absolutely convergent. (This differs slightly from the usual definition where a lower limit of

for which the integral is absolutely convergent. (This differs slightly from the usual definition where a lower limit of  is used for the integral. See the note on Mellin transforms at the end of this post.) Now, the map

is used for the integral. See the note on Mellin transforms at the end of this post.) Now, the map  is a continuous homomorphism from the multiplicative group of nonzero reals

is a continuous homomorphism from the multiplicative group of nonzero reals  to

to  ,

,

Denoting  , integration with respect to

, integration with respect to  is invariant under multiplicative rescaling by any

is invariant under multiplicative rescaling by any  ,

,

That is,  is the multiplicative Haar measure on

is the multiplicative Haar measure on  , and the Mellin transform is the integral of

, and the Mellin transform is the integral of  against multiplicative characters with respect to the multiplicative Haar measure. This explains why the Fourier transform (8) is additive and the Mellin transform (9) is multiplicative.

against multiplicative characters with respect to the multiplicative Haar measure. This explains why the Fourier transform (8) is additive and the Mellin transform (9) is multiplicative.

For an explicit example of a Mellin transform, consider  ,

,

Here, the substitution  was used. Comparing with the definition (4) of the gamma function,

was used. Comparing with the definition (4) of the gamma function,

|

(10) |

For Schwartz functions, the integral defining the Mellin transform is absolutely convergent on the right half-plane  , and can be analytically continued to the entire complex plane.

, and can be analytically continued to the entire complex plane.

Theorem 3 If  , then

, then  is well defined over

is well defined over  , and uniquely extends to a meromorphic function on

, and uniquely extends to a meromorphic function on  with only simple poles at the non-positive even numbers

with only simple poles at the non-positive even numbers  , with residue

, with residue

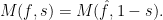

I’ll give a proof of theorem 3 below. For now, we will move straight on to the statement of the functional equation relating the Mellin transform of  to that of its Fourier transform

to that of its Fourier transform  .

.

Theorem 4 If  then

then  extends to a meromorphic function with only simple poles at

extends to a meromorphic function with only simple poles at  and

and  of residue

of residue  and

and  respectively. The functional equation

respectively. The functional equation

|

(11) |

holds everywhere.

A proof of this will be given further down. It can be shown that the specific case  is equal to its own Fourier transform,

is equal to its own Fourier transform,  . So, using expression (10) for the Mellin transform

. So, using expression (10) for the Mellin transform  , we see that Riemann’s functional equation follows directly from (11).

, we see that Riemann’s functional equation follows directly from (11).

Above, we discussed how Riemann’s functional equation allows values of  to be determined on the left half-plane

to be determined on the left half-plane  and restricts the locations of its zeros to be as described in lemma 2. This made use of properties of the gamma function, specifically the locations of its poles and the fact that it has no zeros. These arguments can be made by instead using version (11) of the functional equation, and the gamma function need not be referred to at all. For an arbitrary smooth function

and restricts the locations of its zeros to be as described in lemma 2. This made use of properties of the gamma function, specifically the locations of its poles and the fact that it has no zeros. These arguments can be made by instead using version (11) of the functional equation, and the gamma function need not be referred to at all. For an arbitrary smooth function  , theorem 3 gives the poles of

, theorem 3 gives the poles of  . Also, by choosing

. Also, by choosing  with compact support in

with compact support in  ,

,  will be well-defined everywhere by (9) and is analytic. It is also easy to choose

will be well-defined everywhere by (9) and is analytic. It is also easy to choose  such that the Mellin transform does not vanish at any specified point, which is enough to apply the arguments above.

such that the Mellin transform does not vanish at any specified point, which is enough to apply the arguments above.

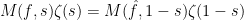

I now briefly consider the relation between the functional equation in the form (11) and the ideas of John Tate’s 1950 thesis. Theorem 4 can be viewed primarily as relating the Mellin transform of the Fourier transform to the Mellin transform of the original function. The zeta function plays more of an ancillary role as a multiplicative factor in this identity. This treatment of the Mellin transform as the primary object of interest was taken much further in Tate’s thesis. Tate refocussed attention from the rational and real number fields (or algebraic number field) to the larger ring of adeles,  . This is outside of the scope of this post, but the important properties are that, just like the embedding of the rationals inside the reals,

. This is outside of the scope of this post, but the important properties are that, just like the embedding of the rationals inside the reals,  embeds in

embeds in  , and the theory of Fourier and Mellin transforms extends to functions defined on the adeles. In the adelic case, he obtained the functional equation

, and the theory of Fourier and Mellin transforms extends to functions defined on the adeles. In the adelic case, he obtained the functional equation

|

(12) |

Now, the zeta function does not appear at all! Digging a bit deeper, the ring of adeles over the rational numbers can be expressed as a product of the reals and the ring of `finite’ adeles,

That is, every element  of the adelic ring can be expressed as a pair

of the adelic ring can be expressed as a pair  consisting of a real number

consisting of a real number  and a finite adele

and a finite adele  . For a function

. For a function  which is a product of the real and finite parts,

which is a product of the real and finite parts,  , the Mellin and Fourier transforms are also products of the transforms of the individual components.

, the Mellin and Fourier transforms are also products of the transforms of the individual components.

Applying this to the adelic functional equation (12),

Just as the special case  lead to the gamma factor in Riemann’s functional equation, choosing a particular example for the function

lead to the gamma factor in Riemann’s functional equation, choosing a particular example for the function  on the finite adeles which equals its own Fourier transform leads to the appearance of the zeta function in (5) and (11). This places the gamma term and the zeta term in the functional equation on a roughly equal footing.

on the finite adeles which equals its own Fourier transform leads to the appearance of the zeta function in (5) and (11). This places the gamma term and the zeta term in the functional equation on a roughly equal footing.

We can go further. The finite adeles can be broken down into a restricted product of fields corresponding to each prime number — the  -adic numbers,

-adic numbers,

In the case where the function  factors into a product of functions on the

factors into a product of functions on the  -adic components,

-adic components,  , then the Mellin transform commutes with this factorisation,

, then the Mellin transform commutes with this factorisation,

For a particular choice of  , specifically the indicator function of the integral adeles, this is just the Euler product described above. From this viewpoint, the gamma factor in Riemann’s functional equation, the Mellin transform appearing in (11), the Riemann zeta function, and the

, specifically the indicator function of the integral adeles, this is just the Euler product described above. From this viewpoint, the gamma factor in Riemann’s functional equation, the Mellin transform appearing in (11), the Riemann zeta function, and the  terms in the Euler product, are all just manifestations of factorizations of the Mellin transform on the adeles, which itself satisfies the functional equation (12).

terms in the Euler product, are all just manifestations of factorizations of the Mellin transform on the adeles, which itself satisfies the functional equation (12).

Finally, we note that there is an intimate connection between additive and multiplicative structures pervading the above discussion. The natural numbers, which are generated under addition by the unit element  , are also generated under multiplication by the prime numbers. This is reflected in the definition of the zeta function as a sum over the natural numbers (1), which is equivalent to the multiplicative definition given by the Euler product (2). Then, the functional equation (11) ties together the additive Fourier transform over

, are also generated under multiplication by the prime numbers. This is reflected in the definition of the zeta function as a sum over the natural numbers (1), which is equivalent to the multiplicative definition given by the Euler product (2). Then, the functional equation (11) ties together the additive Fourier transform over  with the multiplicative Mellin transform over

with the multiplicative Mellin transform over  .

.

Elementary Inequalities

Above, I stated a few results but, now, let’s move on and actually prove a few things regarding the Riemann zeta function. As this post is not assuming any prior understanding of  , I start at a very basic level and will derive a few elementary inequalities. By elementary, I mean things which can be proved straight from the definition (1) of the zeta function. These will be rather basic and far from optimal — especially in the critical strip — but are easy to prove and give some understanding of what the zeta function looks like.

, I start at a very basic level and will derive a few elementary inequalities. By elementary, I mean things which can be proved straight from the definition (1) of the zeta function. These will be rather basic and far from optimal — especially in the critical strip — but are easy to prove and give some understanding of what the zeta function looks like.

First, for any positive real  , the function

, the function  is decreasing, giving

is decreasing, giving

for any positive integer  with

with  . Integrating over

. Integrating over  and substituting in the definition of

and substituting in the definition of  for

for  ,

,

Substituting in the value  for the integral gives the following bounds.

for the integral gives the following bounds.

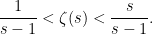

Lemma 5 The sum (1) converges absolutely at all real  , and satisfies the bound

, and satisfies the bound

|

(13) |

In particular,  as

as  approaches

approaches  from above.

from above.

Moving on to  , we can use the identity

, we can use the identity  , where

, where  is the real part of

is the real part of  , to write,

, to write,

Comparing the right hand side with the definition of  , we get,

, we get,

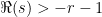

Lemma 6 The sum (1) converges absolutely at all  with

with  and satisfies the bound

and satisfies the bound

where  .

.

The right-hand inequality here is just an application of (13). In particular, lemma 6 implies that  is uniformly bounded on the half-plane

is uniformly bounded on the half-plane  , any

, any  , with the bound

, with the bound  . It also shows that

. It also shows that  uniformly as

uniformly as  .

.

Next, the Euler product expansion (2) can be utilized to show that  has no zeros on the open right half-plane

has no zeros on the open right half-plane  . Applying the inequality

. Applying the inequality  , which applies for all

, which applies for all  ,

,

with  . Noting that the right hand side is just the reciprocal of the Euler product of

. Noting that the right hand side is just the reciprocal of the Euler product of  gives a lower bound.

gives a lower bound.

Lemma 7 The zeta function  is nonzero everywhere on the domain

is nonzero everywhere on the domain  and satisfies the lower bound,

and satisfies the lower bound,

|

(14) |

with  .

.

The right-hand inequality here is another direct application of (13). Lemma 7 shows that  is uniformly bounded away from zero on the half-plane

is uniformly bounded away from zero on the half-plane  , for any

, for any  .

.

Expression (3) for the logarithm of the zeta function can be used to obtain further bounds. On the half-plane  , we use

, we use  ,

,

So, we have obtained the following.

Lemma 8 The logarithm of the zeta function over  satisfies the bound

satisfies the bound

Applying this bound to  gives (14) as a special case.

gives (14) as a special case.

Using  to denote the floor function, we can use the equality

to denote the floor function, we can use the equality  for

for  and each positive integer

and each positive integer  to rewrite the summation (1) as an integral

to rewrite the summation (1) as an integral

Substituting in the value  for the first integral on the right hand side gives the following expression for the zeta function,

for the first integral on the right hand side gives the following expression for the zeta function,

|

(15) |

The idea is of that the integrand here is small in comparison to  , so that we can expect it to converge on a larger domain than the sum (1). In fact, as we will show, it is absolutely integrable on

, so that we can expect it to converge on a larger domain than the sum (1). In fact, as we will show, it is absolutely integrable on  . As uniform limits of analytic functions are analytic, this will extend

. As uniform limits of analytic functions are analytic, this will extend  to an analytic function on this domain.

to an analytic function on this domain.

To bound the integrand in (15), note that  has the derivative

has the derivative  with respect to

with respect to  . Using

. Using  , this has norm

, this has norm  and, as it is decreasing in

and, as it is decreasing in  , is bounded above by

, is bounded above by  . Hence, the mean value theorem gives the inequality

. Hence, the mean value theorem gives the inequality

which will be strict whenever  is not an integer. For any positive integer

is not an integer. For any positive integer  , we have

, we have  on the interval

on the interval  and,

and,

Summing over  and comparing with the definition of

and comparing with the definition of  gives a finite value, so we have proved the following.

gives a finite value, so we have proved the following.

Lemma 9 The zeta function  extends to a meromorphic function on

extends to a meromorphic function on  with a simple pole of residue

with a simple pole of residue  at

at  , and is given by the absolutely convergent integral (15). Furthermore, on this domain, it satisfies the bound

, and is given by the absolutely convergent integral (15). Furthermore, on this domain, it satisfies the bound

|

(16) |

with  .

.

The final inequality here is yet another application of (13). So, we have a bound for  of size

of size  on the right half-plane

on the right half-plane  , for any

, for any  . This is by no means optimal, and it can be improved to

. This is by no means optimal, and it can be improved to  , with even better bounds given by the — as yet — unproven Lindelöf hypothesis.

, with even better bounds given by the — as yet — unproven Lindelöf hypothesis.

Applying inequality (16) for real  in the interval

in the interval  shows that

shows that  does not vanish,

does not vanish,

Corollary 10  , so is nonzero, on the real line segment

, so is nonzero, on the real line segment  .

.

Interestingly, this bound is optimal, as  .

.

Elementary Extension of the Zeta Function

I will now describe an elementary method of analytically continuing the Riemann zeta function to the entire complex plane. Nothing in this section is required for the results discussed above, so can be skipped if required. The reason for including it here is to gain an intuitive understanding why the definition (1) of  given on the half-plane

given on the half-plane  should continue to all of

should continue to all of  , without using any `magic’ formulas such as Poisson summation or the functional equation. Instead, we can use the Euler-Maclaurin formula. Rather than just stating and applying this equation, I will derive it, as it is straightforward to do and gives a better understanding of why the zeta function necessarily extends to the complex plane.

, without using any `magic’ formulas such as Poisson summation or the functional equation. Instead, we can use the Euler-Maclaurin formula. Rather than just stating and applying this equation, I will derive it, as it is straightforward to do and gives a better understanding of why the zeta function necessarily extends to the complex plane.

We can apply a similar ideas to that which was used to express  over

over  by identity (15). To do this in more generality, I will look at a sum

by identity (15). To do this in more generality, I will look at a sum  for a smooth function

for a smooth function  . Some assumptions will be required on

. Some assumptions will be required on  in order that the sums and integrals converge, so suppose that it is smooth and that its derivatives to all orders are integrable over

in order that the sums and integrals converge, so suppose that it is smooth and that its derivatives to all orders are integrable over  . This is the case for the Riemann zeta function where

. This is the case for the Riemann zeta function where  .

.

For a differentiable function  defined on the interval

defined on the interval ![{[0,1]}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7B%5B0%2C1%5D%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002) , an integration by parts gives

, an integration by parts gives

for any constant  . The idea is to replace

. The idea is to replace  by

by  in this identity and sum over

in this identity and sum over  . In order that

. In order that  has average value

has average value  over the unit interval, we will take

over the unit interval, we will take  . So, setting

. So, setting  ,

,

|

(17) |

with  denoting the fractional part of

denoting the fractional part of  . That is

. That is  on the interval

on the interval  . The hope here is that

. The hope here is that  is sufficiently smaller then

is sufficiently smaller then  , so that the right-hand integral converges even when the sum on the left diverges.

, so that the right-hand integral converges even when the sum on the left diverges.

We take this a step further and express the integral over  as an integral over

as an integral over  . Again, consider a function

. Again, consider a function  defined on the unit interval and, choosing

defined on the unit interval and, choosing  to be the integral of

to be the integral of  , another integration by parts gives

, another integration by parts gives

As  has zero integral,

has zero integral,  , so replacing

, so replacing  by

by  and summing over

and summing over  ,

,

Again,  is only defined up to an arbitrary constant, so can be chosen to have zero integral over the unit interval.

is only defined up to an arbitrary constant, so can be chosen to have zero integral over the unit interval.

We repeat this procedure  times and substitute into (17),

times and substitute into (17),

|

(18) |

Here,  is defined as the integral of

is defined as the integral of  with constant of integration chosen such that it has zero integral over the unit interval,

with constant of integration chosen such that it has zero integral over the unit interval,

From this definition, it can be seen that  where

where  are the Bernoulli polynomials,

are the Bernoulli polynomials,  for Bernoulli numbers

for Bernoulli numbers  , and (18) is the Euler-Maclaurin formula.

, and (18) is the Euler-Maclaurin formula.

In particular, the derivatives of  can be computed as

can be computed as

with  denoting the rising factorial, which is just a polynomial in

denoting the rising factorial, which is just a polynomial in  .

.

Taking  for

for  , the left hand side of identity (18) is

, the left hand side of identity (18) is  and the first integral on the right is

and the first integral on the right is  . Applying this to definition (1) of the zeta function,

. Applying this to definition (1) of the zeta function,

|

(19) |

As the integral on the right converges absolutely on  , and

, and  is an arbitrary positive integer, we have the analytic extension.

is an arbitrary positive integer, we have the analytic extension.

Theorem 11 The function  defined on

defined on  by (1) continues to a meromorphic function on

by (1) continues to a meromorphic function on  with a single simple pole at

with a single simple pole at  of residue

of residue  .

.

Furthermore, the integral on the right of (19) is uniformly bounded over  , any

, any  , and the

, and the  terms are polynomials, so we have the following bound on the growth of the zeta function.

terms are polynomials, so we have the following bound on the growth of the zeta function.

Lemma 12 For every real number  , there exists an

, there exists an  such that

such that

over  , as

, as  .

.

I purposefully did not put in any specific value for  here, as the point is that the zeta function is polynomially bounded on each right half-plane and, in any case, there are more optimal values available from applying the functional equation.

here, as the point is that the zeta function is polynomially bounded on each right half-plane and, in any case, there are more optimal values available from applying the functional equation.

Mellin Transforms

We show that the Mellin transform of a Schwartz function  can be continued from the region

can be continued from the region  to the entire complex plane, proving theorem 3. Choosing a positive integer

to the entire complex plane, proving theorem 3. Choosing a positive integer  , write

, write

This is bounded, and for  is just the remainder term in the Taylor polynomial approximation of

is just the remainder term in the Taylor polynomial approximation of  . By Taylor’s theorem,

. By Taylor’s theorem,  as

as  approaches

approaches  . So,

. So,  is absolutely integrable on

is absolutely integrable on  and, hence,

and, hence,  is a well-defined analytic function on this domain. The transform of the polynomial term can be computed,

is a well-defined analytic function on this domain. The transform of the polynomial term can be computed,

The Mellin transform of  is then,

is then,

This statement holds for  but, as the right hand side is a well-defined meromorphic function on

but, as the right hand side is a well-defined meromorphic function on  , it extends

, it extends  to a meromorphic function on this domain. The poles arise from the

to a meromorphic function on this domain. The poles arise from the  terms with the residue stated in theorem 3. By choosing

terms with the residue stated in theorem 3. By choosing  arbitrarily large, we have the extension to the complex plane.

arbitrarily large, we have the extension to the complex plane.

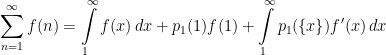

Poisson Summation

The second proof of the functional equation given by Riemann in his 1859 paper made use of the following identity of Jacobi,

For the Mellin transform version of the functional equation, we make use of the Poisson summation formula. To avoid having to explicitly write limits everywhere, the notation  is used to denote the sum as

is used to denote the sum as  ranges over the integers

ranges over the integers  .

.

Theorem 13 If  has Fourier transform

has Fourier transform  then,

then,

|

(20) |

Jacobi’s identity is just a special case of this using  . The Poisson summation formula can be proved using Fourier series. The idea is that, for any Schwartz function

. The Poisson summation formula can be proved using Fourier series. The idea is that, for any Schwartz function  , we can define a periodic

, we can define a periodic  by

by

|

(21) |

Since  and its derivatives vanish rapidly at

and its derivatives vanish rapidly at  , this sum is uniformly convergent, with smooth limit. Writing out its Fourier expansion,

, this sum is uniformly convergent, with smooth limit. Writing out its Fourier expansion,

the Fourier coefficients can be evaluated,

Substituting into (21) proves theorem 13.

In practise, it is convenient to express the Poisson summation formula in a slightly more general way. For each fixed  , the Fourier transform of

, the Fourier transform of  is equal to

is equal to  and, putting this in (20), gives the following alternative statement of Poisson summation.

and, putting this in (20), gives the following alternative statement of Poisson summation.

Theorem 14 If  has Fourier transform

has Fourier transform  then, for any

then, for any  ,

,

|

(22) |

The Functional Equation

The proof of the functional equation starts with the following identity

Here,  is any nonzero integer,

is any nonzero integer,  is a Schwartz function on the reals,

is a Schwartz function on the reals,  , and

, and  represents the Haar measure on the multiplicative group

represents the Haar measure on the multiplicative group  . The identity is achieved simply by substituting

. The identity is achieved simply by substituting  with

with  . Restricting to

. Restricting to  , we can sum over

, we can sum over  ,

,

|

(23) |

What we would really like to do here is to simply substitute in (22) for the sum of  , substitute

, substitute  by

by  in the integral, and immediately derive the functional equation (11). Unfortunately this leads to divergent sums and integrals. Instead, start by rearranging (22) as

in the integral, and immediately derive the functional equation (11). Unfortunately this leads to divergent sums and integrals. Instead, start by rearranging (22) as

We will apply this to the integrand in (23), but only over the range with  .

.

Here, we substituted  for

for  in the first term on the right hand side, and used the exact value for the integral in the other two terms. Using this in (23),

in the first term on the right hand side, and used the exact value for the integral in the other two terms. Using this in (23),

|

(24) |

As  vanishes faster than any power of

vanishes faster than any power of  at infinity, the sum

at infinity, the sum  is absolutely convergent and also vanishes faster than any power of

is absolutely convergent and also vanishes faster than any power of  . The same statement holds for

. The same statement holds for  , so the integral in (24) is defined for all

, so the integral in (24) is defined for all  and is analytic. This extends

and is analytic. This extends  to a meromorphic function on the complex plane with poles and residues as stated in theorem 4. Finally, noting that the Fourier transform of

to a meromorphic function on the complex plane with poles and residues as stated in theorem 4. Finally, noting that the Fourier transform of  is

is  , the right hand side of (24) is unchanged if

, the right hand side of (24) is unchanged if  is replaced by

is replaced by  and

and  is replaced by

is replaced by  , proving the functional equation (11).

, proving the functional equation (11).

A Note on Mellin Transforms

The Mellin transform was defined above as an integral over the real numbers (9), which deviates slightly from the more usual definition as an integral over the positive reals,

The reason for using the alternative definition is that we were interested in the functional equation relating it to the Fourier transform defined over the reals, so also required the Mellin transform to be defined with the same domain of integration. However, in doing so, we lose some properties, such as the existence of an inversion formula which, for the usual Mellin transform, is

for any fixed  in the domain where the Mellin transform is absolutely integrable.

in the domain where the Mellin transform is absolutely integrable.

The transform defined by (9) is unchanged if  is replaced by

is replaced by  , so is not one-to-one and cannot be inverted. The best that can be done is to recover the even part of

, so is not one-to-one and cannot be inverted. The best that can be done is to recover the even part of  ,

,

An explanation for the non-invertibility of the Mellin transform defined over  is that we did not consider the full set of characters. We only looked at characters of the form

is that we did not consider the full set of characters. We only looked at characters of the form  but, for example, this excludes the function

but, for example, this excludes the function  mapping positive reals to

mapping positive reals to  and negative reals to

and negative reals to  . More generally, for any

. More generally, for any  and

and  , a character

, a character  can be defined by

can be defined by

|

(25) |

It is immediate that this is a continuous map from the nonzero reals to  satisfying

satisfying  . In fact, it can shown that (25) gives the full set of characters on

. In fact, it can shown that (25) gives the full set of characters on  . The characters given by

. The characters given by  , which we made use of in the discussion above, are precisely those which are trivial on the roots of unity

, which we made use of in the discussion above, are precisely those which are trivial on the roots of unity  and are called unramified characters. Those given by

and are called unramified characters. Those given by  are called ramified.

are called ramified.

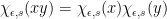

The Mellin transform with respect to an arbitrary character  is

is

The transform defined using the full set of characters can be inverted,

The argument given above, including the proof of the functional equation (11), could have been carried out with the full set of characters. In that case, the zeta function is replaced by

For the unramified characters,  , this is the usual Riemann zeta function. For ramified characters,

, this is the usual Riemann zeta function. For ramified characters,  equals

equals  and the functional equation reduces to the trivial statement

and the functional equation reduces to the trivial statement  . So, there was nothing to be gained by including ramified characters in the discussion.

. So, there was nothing to be gained by including ramified characters in the discussion.