From the definition of standard Brownian motion B, given any positive constant c, will be normal with mean zero and variance c(t–s) for times

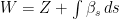

. So, scaling the time axis of Brownian motion B to get the new process

just results in another Brownian motion scaled by the factor

.

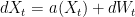

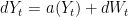

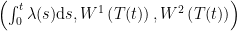

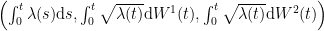

This idea is easily generalized. Consider a measurable function and Brownian motion B on the filtered probability space

. So,

is a deterministic process, not depending on the underlying probability space

. If

is finite for each

then the stochastic integral

exists. Furthermore, X will be a Gaussian process with independent increments. For piecewise constant integrands, this results from the fact that linear combinations of joint normal variables are themselves normal. The case for arbitrary deterministic integrands follows by taking limits. Also, the Ito isometry says that

has variance

So, has the same distribution as the time-changed Brownian motion

.

With the help of Lévy’s characterization, these ideas can be extended to more general, non-deterministic, integrands and to stochastic time-changes. In fact, doing this leads to the startling result that all continuous local martingales are just time-changed Brownian motion.

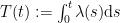

Defining a stochastic time-change involves choosing a set of stopping times such that

whenever

. Then,

defines a new, time-changed, filtration. Applying the same change of time to a process X results in the new time-changed process

. If X is progressively measurable with respect to the original filtration then

will be

-adapted. The time-change is continuous if

is almost surely continuous. By the properties of quadratic variations, the following describes a continuous time-change.

Theorem 1 Any continuous local martingale X with

is a continuous time-change of standard Brownian motion (possibly under an enlargement of the probability space).

More precisely, there is a Brownian motion B with respect to a filtration

such that, for each

,

is a

-stopping time and

.

In particular, if W is a Brownian motion and is W-integrable then the result can be applied to

. As

this gives

for a Brownian motion B. This allows us to interpret the integral as a Brownian motion with time run at rate

.

The conclusion of Theorem 1 only holds in a possible enlargement of the probability space. To see why this condition is necessary, consider the simple example of a local martingale X which is identically equal to zero. In this case, it is possible that the underlying probability space is trivial, so does not contain any non-deterministic random variables at all. It is therefore necessary to enlarge the probability space to be able to assert the existence of at least one Brownian motion. In fact, this will be necessary whenever has nonzero probability of being finite. As stated in Theorem 1, only enlargements of the probability space are required, not of the filtration

. That is, we consider a probability space

and a measurable onto map

preserving probabilities, so

for all

. Any processes on the original probability space can then be lifted to

. The filtration is also lifted to

. In this way, it is always possible to enlarge the probability space so that Brownian motions exist. For example, if

is a probability space on which there is a Brownian motion defined, we can take

,

and

for the enlargement, and

is just the projection onto

.

Theorem 1 is a special case of the following time-change result for multidimensional local martingales. A d-dimension continuous local martingale is a time change of Brownian motion if the quadratic variation is proportional to the identity matrix. Below,

denotes the Kronecker delta.

Theorem 2 Let

be a continuous local martingale with

. Suppose, furthermore, that

for some process A and all

and

. Then, under an enlargement of the probability space, X is a continuous time-change of standard d-dimensional Brownian motion.

More precisely, there is a d-dimensional Brownian motion B with respect to a filtration

such that, for each

,

is a

-stopping time and

.

Proof: Define stopping times

and the filtration , for all

. The stopped processes

have quadratic variation

. So, they are

-bounded martingales, and the limit

exists almost surely. By optional sampling,

for all , so Z is a martingale. From the definition,

is left-continuous and A is constant with value t on the interval

. Then, as the intervals of constancy of

coincide with those of

, it follows that

, and Z is continuous.

Next, is a local martingale. As

is square integrable it follows that

are uniformly integrable martingales. Applying optional sampling as above and substituting in

shows that

is a martingale with respect to . If it is known that

, then Lévy’s characterization says that Z is a standard d-dimensional Brownian motion. More generally, enlarging the probability space if necessary, we may suppose that there exists some d-dimensional Brownian motion W independently of

. Then,

is a martingale under its natural filtration, with covariations

. So,

is a local martingale.

Then, and

are local martingales under the filtration

jointly generated by

and M. So, by Levy’s characterization, B is a standard d-dimensional Brownian motion. For any

, A is constant on the interval

. So, X is also constant on this interval giving,

It only remains to be shown that is a

-stopping time. For any times

the definition of

gives

As this holds for all u, , and

is a

-stopping time. ⬜

So, all continuous local martingales are continuous time changes of standard Brownian motion. The converse statement is much simpler and, in fact, the local martingale property is preserved under continuous time-changes.

Lemma 3 Let X be a local martingale and

be finite stopping times such that

is continuous and increasing.

Then,

is a local martingale with respect to the filtration

.

Proof: Choose stopping times such that the stopped processes

are uniformly integrable martingales. Then, set

Continuity of gives

, and

as n goes to infinity. For each

,

implies that is a

-stopping time. Finally,

is a uniformly integrable process and optional sampling gives

So, is a local martingale with respect to

. ⬜

Finally for this post, we show that stochastic integration transforms nicely under continuous time-changes. Under a time-change defined by stopping times the integral transforms as

We have to be a bit careful here, as the integral on the left hand side is defined with respect to a different filtration than on the right. The precise statement is as follows.

Lemma 4 Let X be a semimartingale and

be a predictable, X-integrable process. Suppose that

are finite stopping times such that

is continuous and increasing. Define the time-changes

,

and

.

With respect to the filtration

,

is a semimartingale,

is predictable and

-integrable, and

(1)

Proof: First, as is continuous, changing time takes the set of

-adapted and left-continuous (resp. cadlag) processes to the set of

-adapted and left-continuous (resp. cadlag) processes . However, the predictable sigma algebra is generated by the adapted left-continuous processes, so the time-change takes

-predictable processes to

-predictable processes. Therefore, with respect to

,

is predictable and

is a cadlag adapted processes.

If is elementary predictable, then (1) follows immediately from the explicit expression for the integral. Once it is known that

is a semimartingale, dominated convergence for stochastic integration will imply that the set of bounded predictable processes

for which (1) is satisfied will be closed under pointwise convergence of bounded sequences. So, by the monotone class theorem, the result holds for all bounded predictable

.

To show that is a semimartingale, it is necessary to show that it is possible to define stochastic integration for bounded predictable integrands such that the explicit expression for elementary integrals and bounded convergence in probability are satisfied. We can use (1) to define the integral. Let us set

which, by the Debut theorem, will be an -stopping time and

. Also,

is left-continuous. Suppose that we are given a left-continuous and adapted process

with respect to

then, for each

,

will be left-continuous and adapted with respect to

. Therefore

will be predictable. More generally, this holds for any -predictable

. Also,

, so

, except on intervals for which

(and hence

) is constant. So, when they are elementary predictable, equation (1) holds with these values of

and

.

We then use (1) to define the stochastic integral for bounded

-predictable

. By the dominated convergence theorem for integration with respect to X, it follows that the integral we have defined with respect to

satisfies bounded convergence in probability, as required. So

is indeed an

-semimartingale.

Equation (1) can be generalized to arbitrary X-integrable by making use of associativity of stochastic integration. Let

be X-integrable and set

and

. Then,

is an

-semimartingale and, setting

,

gives

Here, (1) has been applied to the bounded integrands and

. Integrating

with respect to both sides shows that

is

-integrable and

as required. ⬜

Hi,

looking for time changes of Brownian motion I stumbled on your site. It’s amazing! =)

I wonder about the first eqnarray: the last equality being .

.

I cannot see this right away, what am I missing?

Best regards,

Konsta

Hm, returning, it looks like applying Ito-Isometry backwards. I think I’ve sorted out my difficulties with that equality.

Hi Konsta, and welcome!

There’s no need to use anything as advanced as the Ito isometry for this equality. By definition, if B is a Brownian motion and , then

, then  has mean 0 and variance t-s. So,

has mean 0 and variance t-s. So, ![\mathbb{E}[(B_t-B_s)^2]=t-s](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathbb%7BE%7D%5B%28B_t-B_s%29%5E2%5D%3Dt-s&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002) . I just replaced t by

. I just replaced t by  and s by

and s by  .

.

Hi,

thank you for this very interesting post !

I recently had to deal with the following situation, and was wondering if you could shed some light on it ? and two nice random processes (suppose any regularity you want – but they are random)

and two nice random processes (suppose any regularity you want – but they are random)  . The process

. The process  is a semi-martingale, and after a Girsanov-like change of probability we can see that under another probability

is a semi-martingale, and after a Girsanov-like change of probability we can see that under another probability  , the process

, the process  is a continuous martingale with quadratic variation

is a continuous martingale with quadratic variation  . It is very tempting to say that there is a

. It is very tempting to say that there is a  -Brownian motion

-Brownian motion  (adapted to the same filtration as

(adapted to the same filtration as  ) such that

) such that  , with the same process

, with the same process  .

.

Consider a Brownian motion

Is this true ?

Best

Alekk

Welcome Alekk.

The quick answer to your question is Yes!

Under an equivalent measure , W will decompose as

, W will decompose as  for a

for a  -Brownian motion Z. Then,

-Brownian motion Z. Then,  , where X and

, where X and  are both

are both  -local martingales. By uniqueness of the decomposition into continuous local martingale and FV components,

-local martingales. By uniqueness of the decomposition into continuous local martingale and FV components,  .

.

Coincidentally, my next post is going to be on Girsanov transforms, which I’ll probably put up tomorrow.

Thank you! to

to  .

.

I did not think to use this uniqueness of the decomposition. I was using this result while trying to re-prove the Girsanov change of probability to go from a SDE

Best

Alekk

Hi Alekk,

I had a look at your comment and checked Oksendal’s book: I believe Theorem 8.6.4 (The Girsanov theorem II) on page 157 in my version of the book applies directly to a special case of your question (set alpha=0). Does this help?

Btw: In my comment I meant the in Oksendal, not the

in Oksendal, not the  in your comment.

in your comment.

Hi again,

since I was interested in the relation of the time-change Ito integral and the time-changed Brownian motion

and the time-changed Brownian motion  , I tried to prove their mean-square equality and I am quite sure they are not. So, while they seem to have the same distribution, they are not equal in general (in the mean-square sense). Do you agree or disagree?

, I tried to prove their mean-square equality and I am quite sure they are not. So, while they seem to have the same distribution, they are not equal in general (in the mean-square sense). Do you agree or disagree?

They are not what? The processes are definitely not equal, but they do have the same distribution.

btw, I’m not sure what you mean by the “time-change Ito integral”. The integral does not involve a time change.

does not involve a time change.

ad “They are not what?”: – actually I’m not sure which equality sign this is in case of stochastic calculus – but usually it’s not just equality in distribution.

– actually I’m not sure which equality sign this is in case of stochastic calculus – but usually it’s not just equality in distribution.

They are not equal in mean-square sense. Basically I’d like to write

ad “time-change Ito integral”: and I called it such because I think of it as

and I called it such because I think of it as  where

where  and

and  are most likely different Brownian motions.

are most likely different Brownian motions.

I meant the integral

Well is a local martingale with quadratic variation

is a local martingale with quadratic variation  . So, using Theorem 1,

. So, using Theorem 1,  for some Brownian motion W. However, W is not the same as B. In fact, it is defined with respect to a different filtration

for some Brownian motion W. However, W is not the same as B. In fact, it is defined with respect to a different filtration  . The point is that the integral has the same distribution as a time-change of a Brownian motion.

. The point is that the integral has the same distribution as a time-change of a Brownian motion.

Also, I made a typo. should be replaced by

should be replaced by  in the post. I’ll fix this.

in the post. I’ll fix this.

btw, to post latex in a comment, use $latex … $. Just using dollar signs doesn’t work.

The function \xi in the second paragraph can take negative values….no? Why the restriction to R_+?

p.s. I mean in the range, of course. So, this would mean you can express things as the square root, but that isn’t important. What matters is that \theta = int \xi^2 . Because of the square, the range of \xi is irrelevant, right?

Ooops…I mean that “..you can’t express things…”

Yes it can take negative values. The only reason I restricted to nonnegative values is so that the formula a bit further down the paragraph holds. But this is a very minor point, and we don’t really need this identity.

a bit further down the paragraph holds. But this is a very minor point, and we don’t really need this identity.

Dear George Lowther,

We are working with stochastic methods for finanace and are very interested in Theorem 2 above. Compared to the results given e.g. in Protter Theorem 42 and Revuz/Yor Theorem V.1.9, theorem 2 presents an additional result which is the representation of the local martingale X as a time changed Brownian Motion (X_t = B_A_t). Inspite of the fact that the proof is presented above, we would like to have more details of it. Could you help us?

Hi. I should be able to help – I’ll have to check again the references you mention, but I think what I write here is fairly standard. I can drop you an email on the address registered with this comment if you prefer.

Yes, I prefer.

I am looking forward to hearing from you.

Our interest, in fact, is to gain a result for correlated martingales. Do you have results in the correlated scenario?

you have mail!

In several places you require that the time chamge is “increasing.” I take this to mean strictly increasing, rather than nondecreasing. For what steps in the logic is this necessary? Can you recommend a reference for what can be said if they are nondecreasing? More generally, whats your favorite reference for these theorems? Thanks!

Generally, I am using increasing to mean nondecreasing. Perhaps I should have been clearer. For references, I think Rogers & Williams or Revuz & Yor have sections on time changes, although I’ll have to double check my other references.

Dear George Lowther, first of all thank you for your enlightening blog posts. They really help me to deepen my understanding of stochastic calculus. I came of with a question that I was not able to find an answer on and thought that maybe you could provide me with one. I’m currently interested in time changed Levy-models and want to show that an arithmetic Brownian motion time changed by the integral of a CIR-process is equivalent to the Heston-model. To do so, I need to show the following: Let and

and  be two independent Brownian motions and

be two independent Brownian motions and  the CIR SDE. Now define

the CIR SDE. Now define  . I need to show that the laws of the processes

. I need to show that the laws of the processes  and

and  follow the same law. I believe I could use some variant of Dubins-Schwarz theorem. However, I am not sure if the correlation/independence structure is preserved under that change.

follow the same law. I believe I could use some variant of Dubins-Schwarz theorem. However, I am not sure if the correlation/independence structure is preserved under that change.

Thank you for the informative web site.

A question: from Monroe’s Theorem we can represent a cadlag semimartingale as a time-changed Brownian motion (omitting some of the statement). If I understand the theorem, a Poisson process should be representable as a time-changed Brownian motion (as should a compound Poisson process). Has the explicit time change appeared in print?

I didn’t deal with Monroe’s theorem here, and am not familiar with the construction of the time-change in general, but it looks like it shouldn’t be too difficult for the special case of increasing processes.

Hi George, I can’t figure out why in Lemma 3, we have 1_{\tilde{\sigma_n}>0} \tilde{X_t}^{\tilde{\sigma_n}} = 1_{\sigma_n>\tau_0} Y_{\tau_t}^n? From definition, Y_{\tau_t}^n = 1_{\sigma_n>0} X_{\tau_t \wedge \sigma_n} and \tilde{X_t}^{\tilde{\sigma_n}} = X_{\tau_t \wedge \tilde{\sigma_n}}. I can see that 1_{\tilde{\sigma_n}>0} = 1_{\sigma_n>\tau_0}. But 1_{\sigma_n>\tau_0} may not be equal to 1_{\sigma_n>0} and how do we relate X_{\tau_t \wedge \sigma_n} with X_{\tau_t \wedge \tilde{\sigma_n}} here?

Hi George, there are a couple of points I don’t understand in the proof of Lemma 4.

In the final sentences of the third paragraph, how can we justify that this holds for any \tilde{F}-predictable \tilde{\xi}? I assume you mean we can use the same limiting argument, but is \tilde{\xi}_{A_t} still predictable?

Also, in the sentences below, you say A_{\tau_t}=t, so \tilde{\xi}_t=\xi_{\tau_t}, except on intervals for which \tua_t (and hence \tilde{X}_t) is constant. But you define \tilde{\xi}_t:=\xi_{\tau_t}, so I don’t understand why they may not be equal on intervals for which \tau_t is constant. And what happens to equation (1) for elementary predictable \xi and \tilde{\xi} if they are not equal on some intervals? I am confused about the statement that equation (1) holds with these values of \xi and \tilde{\xi} as you say in the first sentence of paragraph 2 that if \xi is elementary predictable, then (1) follows immediately from the explicit expression for the integral.

Finally, in the last sentence, how are we able to integrate \tilde{\alpha}^{-1} with resepct to both sides? We have an equivalence of two integrals \int \tilde{\alpha}\tilde{\xi} d\tilde{X} and \int \tilde{\alpha} d\tilde{Y}.

I don’t understand how we integrate over an integral here.

Hi George,

Thank you for this very detailed page on the time change. Could you please recommand some references on the subject for further readings, or simply some of the references you used for your page. I find it really difficult to find relevant references on the subject

I’ll check my references when home, but I don’t think I used anything outside of Revuz & Yor, Protter and Rogers & Williams

X_t = \exp(At)X_0

\mathbb{E}[(B_t-B_s)^2]=t-s

$ \mathbb{E}[(B_t-B_s)^2]=t-s$