I continue the investigation of discrete barrier approximations started in an earlier post. The idea is to find good approximations to a continuous barrier condition, while only sampling the process at a discrete set of times. The difference now is that I will look at model independent methods which do not explicitly depend on properties of the underlying process, such as the volatility. This will enable much more generic adjustments which can be applied more easily and more widely. I point out now, the techniques that I will describe here are original research and cannot currently be found in the literature outside of this blog, to the best of my knowledge.

Recall that the problem is to compute the expected value of a function of a stochastic process X,

| (1) |

which depends on whether or not the process crosses a continuous barrier level K. In many applications, such as with Monte Carlo simulation, we typically only sample X at a discrete set of times 0 < t1 < t2 < ⋯< tn = T. In that case, the continuous barrier is necessarily approximated by a discrete one

| (2) |

As we saw, this converges slowly as the number n of sampling times increases, with the error between this and the limiting continuous barrier (1) only going to zero at rate 1/√n.

A barrier adjustment as described in the earlier post is able to improve this convergence rate. If X is a Brownian motion with constant drift μ and positive volatility σ, then the discrete barrier level K is shifted down by an amount βσ√δt where β ≈ 0.5826 is a constant and δt = T/n is the sampling width. We are assuming, for now, that the sampling times are equally spaced. As was seen, using the shifted barrier level in (2) improves the rate of convergence. Although we did not theoretically derive the new convergence rate, numerical experiment suggests that it is close to 1/n.

Another way to express this is to shift the values of X up,

| (3) |

Then, (2) is replaced to use these shifted values, which are a proxy for the maximum value of X across each of the intervals (ti-1, ti),

| (4) |

As it is equivalent to shifting the level K down, we still obtain the improved rate of convergence.

This idea is especially useful because of its generality. For non-equally spaced sampling times, the adjustment (3) can still be applied. Now, we just set δt = ti – ti-1 to be the spacing for the specific time, so depends on index i. It can also be used for much more general expressions than (1). Any function of X which depends on whether or not it crosses a continuous barrier can potentially make use of the adjustment described. Even if X is an Ito process with time dependent drift and volatility

| (5) |

the method can be applied. Now, the volatility in (3) is replaced by an average value across the interval (ti-1, ti).

The methods above are very useful, but there is a further improvement that can be made. Ideally, we would not have to specify an explicit value of the volatility σ. That is, it should be model independent. There are many reasons why this is desirable. Suppose that we are running a Monte Carlo simulation and generate samples of X at the times ti. If the simulation only outputs values of X, then this is not sufficient to compute (3). So, it will be necessary to update the program running the simulation to also output the volatility. In some situations this might not be easy. For example, X could be a complicated function of various other processes and, although we could use Ito’s lemma to compute the volatility of X from the other processes, it could be messy. In some situations we might not even have access to the volatility or any method of computing it. For example, the values of X could be computed from historical data. We could be looking at the probability of stock prices crossing a level by looking at historical close fixings, without access to the complete intra-day data. In any case, a model independent discrete barrier adjustment would make applying it much easier.

Removing Volatility Dependence

How can the volatility term be removed from adjustment (3)? One idea is to replace it by an estimator computed from the samples of X, such as

While this would work, at least for a constant volatility process, it does not meet the requirements. For a general Ito process (5) with stochastic volatility, using an estimator computed over the whole time interval [0, T] may not be a good approximation for the volatility at the time that the barrier is hit. A possible way around this is for the adjustment (3) applied at time ti to only depend on a volatility estimator computed from samples near the time. This would be possible, although it is not clear what is the best way to select these times. Besides, an important point to note is that we do not need a good estimate of the volatility, since that is not the goal here.

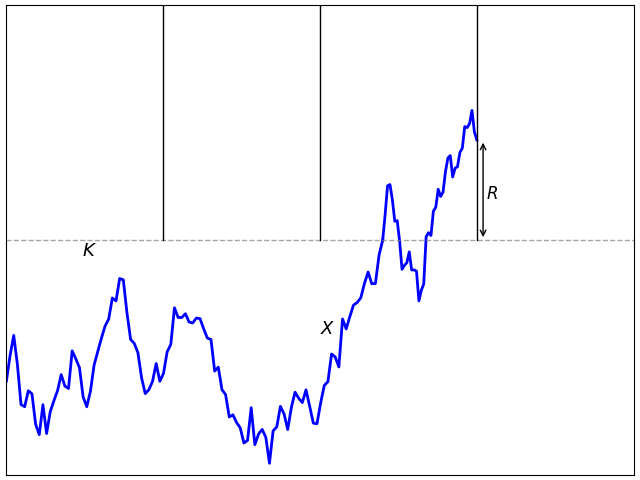

As explained in the previous post, adjustment (3) works because it corrects for the expected overshoot when the barrier is hit. Specifically, at the first time for which Mi ≥ K, the overshoot is R = Xti – K. If there was no adjustment then the overshoot is positive and the leading order term in the discrete barrier approximation error is proportional to 𝔼[R]. The positive shift added to Xti is chosen to compensate for this, giving zero expected overshoot to leading order, and reducing the barrier approximation error. The same applies to any similar adjustment. As long as there is sufficient freedom in choosing Mi, then it should be possible to do it in a way that has zero expected overshoot. Taking this to the extreme, it should be possible to compute the adjustment at time ti using only the sampled values Xti-1 and Xti.

Consider adjustments of the form

for θ: ℝ2 → ℝ. By model independence, if this adjustment applies to a process X, then it should equally apply to the shifted and scaled processes X + a and bX for constants a and b > 0. Equivalently, θ satisfies the scaling and translation invariance,

| (6) |

This restricts the possible forms that θ can take.

Lemma 1 A function θ: ℝ2 → ℝ satisfies (6) if and only if

for constants p, c.

Proof: Write θ(0, u) as the sum of its antisymmetric and symmetric parts

By scaling invariance, the first term on the right is proportional to u and the second is proportional to |u|. Hence,

for constants p and c. Using translation invariance,

as required. ⬜

I will therefore only consider adjustments where the maximum of the process across the interval (ti-1, ti) is replaced by

| (7) |

According to (3), the barrier condition supt≤TXt ≥ K is replaced by the discrete approximation maxiMi ≥ K.

There are various ways in which (7) can be parameterized, but this form is quite intuitive. The term pXti + (1 - p)Xti-1 is an interpolation of the path of X, and c|Xti – Xti-1| represents a shift proportional to the sample deviation across the interval replacing the σ√δt term of the simple shift (3). The purpose of this post is to find values for p and c giving a good adjustment, improving convergence of the discrete approximation.

The discrete barrier condition Mi ≥ K given by (7) can be satisfied while the process is below the barrier level, giving a negative barrier ‘overshoot’ R = Xti – K as in figure 2. As we will see, this is vital to obtaining an accurate approximation for the hitting probability. Continue reading “Model-Independent Discrete Barrier Adjustments”