Continuous local martingales are a particularly well behaved subset of the class of all local martingales, and the results of the previous two posts become much simpler in this case. First, the continuous local martingale property is always preserved by stochastic integration.

Theorem 1 If X is a continuous local martingale and

is X-integrable, then

is a continuous local martingale.

Proof: As X is continuous, will also be continuous and, therefore, locally bounded. Then, by preservation of the local martingale property, Y is a local martingale. ⬜

Next, the quadratic variation of a continuous local martingale X provides us with a necessary and sufficient condition for X-integrability.

Theorem 2 Let X be a continuous local martingale. Then, a predictable process

is X-integrable if and only if

for all

.

Proof: If is X-integrable then the quadratic variation

is finite. Conversely, suppose that V is finite at all times. As X and, therefore, [X] are continuous, V will be continuous. So, it is locally bounded and as previously shown,

is X-integrable. ⬜

In particular, for a Brownian motion B, a predictable process is B-integrable if and only if, almost surely,

for all . Then,

is a continuous local martingale.

Quadratic variations also provide us with information about the sample paths of continuous local martingales.

Theorem 3 Let X be a continuous local martingale. Then,

- X is constant on the same intervals for which [X] is constant.

- X has infinite variation over all intervals on which [X] is non-constant.

Proof: Consider a bounded interval (s,t) for any , and set

for k=0,1,…,n. By the definition of quadratic variation, using convergence in probability,

where V is the variation of X over the interval (s,t). By continuity, tends uniformly to zero as n goes to infinity, so

and [X] is constant over (s,t) whenever the variation V is finite. This proves the second statement of the theorem, which also implies that [X] is constant on all intervals for which X is constant.

It only remains to show that whenever

. Applying this also to the countable set of rational times u in (s,t) will then show that X is constant on this interval whenever [X] is.

The process is a local martingale constant up until s, with quadratic variation

for

. Then

is a stopping time with respect to the right-continuous filtration

and, by stopping,

is a local martingale with zero quadratic variation

. Then, as previously shown,

is a martingale and, therefore,

. This shows that

almost surely. Finally, on the set

, we have

and, hence,

. ⬜

Theorem 3 has the following immediate consequence.

Corollary 4 Any continuous FV local martingale is constant.

Proof: By the second statement of Theorem 3, the quadratic variation [X] is constant. Then, by the first statement, X is constant. ⬜

The quadratic covariation also tells us exactly when X converges at infinity.

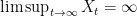

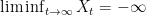

Theorem 5 Let X be a continuous local martingale. Then, with probability one, the following both hold.

exists and is finite whenever

.

and

whenever

.

Proof: By martingale convergence, with probability one either exists and is finite or

and

are both infinite. It just remains to be shown that, with probability one,

exists if and only if

is finite..

Let . Then,

is a local martingale with quadratic variation

bounded by n. So,

and

is an

-bounded martingale which, therefore, almost surely converges at infinity. In particular, on the set

we have outside of a set of zero probability. Therefore,

almost surely exists on

For the converse statement, set . Then,

is a local martingale bounded by n and

. Hence,

is almost surely finite and

is finite on the set

outside of a set of zero probability. Therefore, is almost surely finite on the set

⬜

Theorems 3 and 5 are easily understood once it is known that all local martingales are random time-changes of standard Brownian motion, as will be covered in a later post.

The topology of uniform convergence on compacts in probability (ucp convergence) was introduced in a previous post, along with the stronger semimartingale topology. On the space of continuous local martingales, these two topologies are actually equivalent, and can be expressed in terms of the quadratic variation. Recalling that semimartingale convergence implies ucp convergence and that quadratic variation is a continuous map under the semimartingale topology, it is immediate that the first and third statements below follow from the second. However, the other implications are specific to continuous local martingales.

Lemma 6 Let

and M be continuous local martingales. Then, as n goes to infinity, the following are equivalent.

converges ucp to M.

converges to M in the semimartingale topology.

in probability, for each

.

Proof: As semimartingale convergence implies ucp convergence, the first statement follows immediately from the second. So, suppose that . Write

and let

be the first time at which

. Ucp convergence implies that

tends to infinity in probability, so to prove the third statement it is enough to show that

tends to zero in probability. By continuity, the stopped process

is uniformly bounded by 1, so is a square integrable martingale, and Ito’s isometry gives

as n goes to infinity. The limit here follows from the fact that is bounded by 1 and tends to zero in probability. So, we have shown that

tends to zero in the

norm and, hence, in probability.

Now suppose that the third statement holds. This immediately gives in probability. Letting

be the first time at which

and

be elementary predictable processes, Ito’s isometry gives

So, in particular, in probability. Finally, as

whenever

, which has probability one in the limit

, this shows that

tends to zero in probability and

tends to zero in the semimartingale topology. ⬜

Applying the previous result to stochastic integrals with respect to a continuous local martingale gives a particularly strong extension of the dominated convergence theorem in this case. Note that this reduces convergence of the stochastic integral to convergence in probability of Lebesgue-Stieltjes integrals with respect to .

Theorem 7 Let X be a continuous local martingale and

,

be X-integrable processes. Then, the following are equivalent.

converges ucp to

.

converges to

in the semimartingale topology.

in probability, for each

.

Proof: This follows from applying Lemma 6 to the continuous local martingales and

. ⬜

Theorem 7 also provides an alternative route to constructing the stochastic integral with respect to continuous local martingales. Although, in these notes, we first proved that continuous local martingales are semimartingales and used this to imply the existence of the quadratic variation, it is possible to construct the quadratic variation more directly. Once this is done, the space of X-integrable processes can be defined to be the predictable processes

such that

is almost surely finite for all times t. Define the topology on

so that

if and only if

in probability as

for each t, and use ucp convergence for the topology on the integrals

. Then, Theorem 7 says that

is the unique continuous extension from the elementary integrands to all of

.

Hi, nice blog!

In Theorem 5, what do you mean by [X]_{\infty} < \infty. That the quadratic variation is uniformly bounded by a constant C?

Otherwise your arguments would probably not work? If [X] would only be a.s. finite, then an "n" such that [X] \leq n a.s. would not exist (example: normal random variable takes on only finite values and is therefore a.s. finite but there is no upper bound to the values it takes)…

Is that the way to understand your statement?

Cheers

Chris

No, all that matters is that [X]_\infty < n for some n. n is not fixed, so uniform boundedness is not needed. You don't even need [X]_\infty to be almost surely finite. Even if it is only finite on a set of probability p < 1, X will converge on that set (up to a zero probability set).

Ok, still not sure whether I can follow you.

When [X]_\infty < n for some n and this holds for all \omega in the sample space then it is uniformly bounded by a constant.

When you mean [X]_\infty(\omega) < n(\omega), that is for every element \omega in the sample space you find an n such that [X]_\infty is bounded by n on that given \omega only then the subsequent estimate E[(X^{\tau_n}_t)^2] \leq n does not hold anymore. That estimate would only hold if you have on the right of the estimate something like the ess sup n(\omega), so basically the essential supremum of n over all elements in the sample space. However nothing gurantees you, that this supremum even exists….

I think you’re still misunderstanding my argument. There is no need to be thinking about essential supremums. I’ll try modifying the argument and proof to make it clearer. I’m not able to do this right now as I’m away from my computer (just replying by mobile). Hopefully will have time later tonight.

For now, the theorem could be stated more precisely as follows.

![\displaystyle A=\{\omega\in\Omega: [X]_\infty(\omega) < \infty \}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cdisplaystyle+A%3D%5C%7B%5Comega%5Cin%5COmega%3A+%5BX%5D_%5Cinfty%28%5Comega%29+%3C+%5Cinfty+%5C%7D+&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002)

exists and is finite on A,

exists and is finite on A,  and

and  outside of A.

outside of A.

then, outside of a set of probability zero,

Hey,

a lot clearer now thanks….

Update: I have added a couple of extra results to this post. Lemma 6 shows that ucp convergence, semimartingale convergence and convergence in probability of quadratic variations all coincide. Theorem 7 uses this to give a much stronger version of the dominated convergence theorem for continuous local martingales.

Hi George,

I have been looking for an answer to the following question on continuous local martingales:

Can one construct a non-zero (in sense of having P>0 of being nonzero) continuous local martingale which is identically equal to $0$ P-a.e. at a fixed time $T$? It has to do with an option hedging problem I am working on.

Thanks in advance!

Tigran

Yes! Check out my example of a continuous local martingale which is not a proper martingale from my notes.

Why is the quadratic variation of the stopped process Y^\tau zero?

in the proof of theorem 3

At least, there is an index missing in the definition of \tau.

Right. It should be![[Y]_u](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5BY%5D_u&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002) . I’ll correct the the post in a moment. Thanks

. I’ll correct the the post in a moment. Thanks

I have a question to Theorem 5. Why does [X]^(tau_n) < n implies E[(X^(tau_n))^2] < n ? Thank You 🙂

You always have![\mathbb E[X_t^2]\le\mathbb E[ [X]_t ]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathbb+E%5BX_t%5E2%5D%5Cle%5Cmathbb+E%5B+%5BX%5D_t+%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002) for a local martingale X starting from 0. It follows from Lemma 3 of the post on quadratic variations and the Ito isometry.

for a local martingale X starting from 0. It follows from Lemma 3 of the post on quadratic variations and the Ito isometry.

Hi George, in the proof of Theorem 3, you use a stopping time with respect to the right continuous filtration and claim that Y^\tau is a local martingale (I assume with respect to the right continuous filtration), but why would a local martingale in the original filtration still be a local martingale in the right continuous filtration?

A right-continuous martingale will still be a martingale under the right-continuous filtration. For times s < t < u,![\mathbb E[X_u\vert\mathcal F_t]=X_t](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathbb+E%5BX_u%5Cvert%5Cmathcal+F_t%5D%3DX_t&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002) .

.![\mathbb E[X_u\vert\mathcal F_{s+}]=X_s](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathbb+E%5BX_u%5Cvert%5Cmathcal+F_%7Bs%2B%7D%5D%3DX_s&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002) .

.

Take conditional expectations of this and let t decrease to s to get

Local martingales are right-continuous by definition (in any case, the theorem assumes that it is continuous). Any localizing sequence of stopping times will also be a localizing sequence in the larger filtration, so it remains a local martingale in the right-continuous filtration.