In this post I look at the integral Xt = ∫0t 1{W≥0} dW for standard Brownian motion W. This is a particularly interesting example of stochastic integration with connections to local times, option pricing and hedging, and demonstrates behaviour not seen for deterministic integrals that can seem counter-intuitive. For a start, X is a martingale so has zero expectation. To some it might, at first, seem that X is nonnegative and — furthermore — equals W ∨ 0. However, this has positive expectation contradicting the first property. In fact, X can go negative and we can compute its distribution. In a Twitter post, Oswin So asked about this very point, showing some plots demonstrating the behaviour of the integral.

We can evaluate the integral as Xt = Wt ∨ 0 – 12 Lt0 where Lt0 is the local time of W at 0. The local time is a continuous increasing process starting from 0, and only increases at times where W = 0. That is, it is constant over intervals on which W is nonzero. The first term, Wt ∨ 0 has probability density p(x) equal to that of a normal density over x > 0 and has a delta function at zero. Subtracting the nonnegative value L0t spreads out the density of this delta function to the left, leading to the odd looking density computed numerically in So’s Twitter post, with a peak just to the left of the origin and dropping instantly to a smaller value on the right. We will compute an exact form for this probability density but, first, let’s look at an intuitive interpretation in the language of option pricing.

Consider a financial asset such as a stock, whose spot price at time t is St. We suppose that the price is defined at all times t ≥ 0 and has continuous sample paths. Furthermore, suppose that we can buy and sell at spot any time with no transaction costs. A call option of strike price K and maturity T pays out the cash value (ST - K)+ at time T. For simplicity, assume that this is ‘out of the money’ at the initial time, meaning that S0 ≤ K.

The idea of option hedging is, starting with an initial investment, to trade in the stock in such a way that at maturity T, the value of our trading portfolio is equal to (ST - K)+. This synthetically replicates the option. A naive suggestion which is sometimes considered is to hold one unit of stock at all times t for which St ≥ K and zero units at all other times.The profit from such a strategy is given by the integral XT = ∫0T 1{S≥K} dS. If the stock only equals the strike price at finitely many times then this works. If it first hits K at time s and does not drop back below it on interval (s, t) then the profit at t is equal to the amount St – K that it has gone up since we purchased it. If it drops back below the strike then we sell at K for zero profit or loss, and this repeats for subsequent times that it exceeds K. So, at time T, we hold one unit of stock if its value is above K for a profit of ST – K and zero units for zero profit otherwise. This replicates the option payoff.

The idea described works if ST hits the strike K at a finite set of times,and also if the path of St has finite variation, in which case Lebesgue-Stieltjes integration gives XT = (ST - K)+. It cannot work for stock prices though! If it did, then we have a trading strategy which is guaranteed to never lose money but generates profits on the positive probability event that ST > K. This is arbitrage, generating money with zero risk, which should be impossible.

What goes wrong? First, Brownian motion does not have sample paths with finite variation and will not hit a level finitely often. Instead, if it reaches K then it hits the level uncountably often. As our simple trading strategy would involve buying and selling infinitely often, it is not so easy. Instead, we can approximate by a discrete-time strategy and take the limit. Choosing a finite sequence of times 0 = t0 < t1 < ⋯< tn = T, the discrete approximation is to hold one unit of the asset over the interval (ti, ti+1] if Sti ≥ K and zero units otherwise.

The discrete strategy involves buying one unit of the asset whenever its price reaches K at one of the discrete times and selling whenever it drops back below. This replicates the option payoff, except for the fact then when we buy above K we effectively overpay by amount Sti – K and, when we sell below K, we lose K – Sti. This results in some slippage from not being able to execute at the exact level,

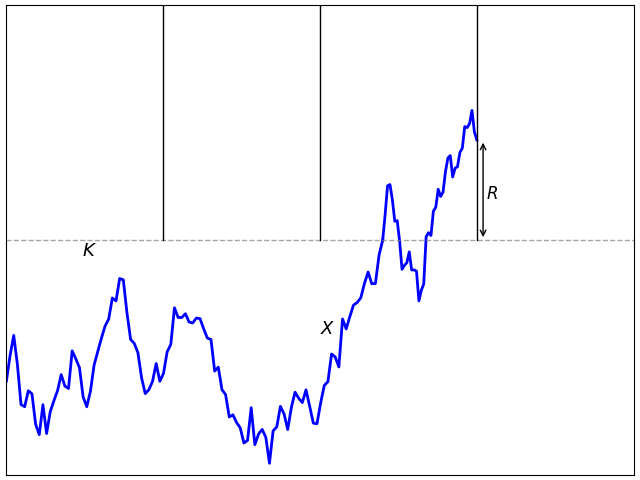

So, our simple trading strategy generates profit (ST - K)+ – AT, missing the option value by amount AT. In the limit as n goes to infinity with time step size going to zero, the slippage AT does not go to zero. For equally spaced times, It can be shown that the number of times that spot crosses K is of order √n, and each of these times generates slippage of order 1/√n on average. So, in the limit, AT does not vanish and, instead, converges on a positive value equal to half the local time LTK.

Figure 2 shows the situation, with the slippage A shown on the same plot (using K as the zero axis, so they are on the same scale). We can just take K = 0 for an asset whose spot price can be positive or negative. Then, with S = W, our integral XT = ∫0T 1{W≥0} dW is the same as the payoff from the naive option hedge, or (ST)+ minus slippage L0T/2.

Now lets turn to a computation of the probability density of XT = WT ∨ 0 – LT0/2. By the scaling property of Brownian motion, the distribution of XT/√T does not depend on T, so we take T = 1 without loss of generality. The first trick to this is to make use of the fact that, if Mt = sups≤tWs is the running maximum then (|Wt|, Lt0) has the same joint distribution as (Mt - Wt, Mt). This immediately tells us that L10 has the same distribution as M1 which, by the reflection principle, has the same distribution as |W1|. Using

for the standard normal density, this shows that the local time L10 has probability density 2φ(x) over x > 0.

Next, as flipping the sign W does not impact either |W1| or L10, sgn(W1) is independent of these. On the event W1 < 0 we have X1 = –L10/2 which has density 4φ(2x) over x < 0. On the event W1 > 0, we have X1 = |W1|-L10/2, which has the same distribution as M1/2 – W1.

To complete the computation of the probability density of X1, we need to know the joint distribution of M1 and W1, which can be done as described in the post on the reflection principle. The probability that W1 is in an interval of width δx about a point x and that M1 > y, for some y > x is, by reflection, equal to the probability that W1 is in an interval of width δx about the point 2y – x. This has probability φ(2y - x)δx and, by differentiating in y, gives a joint probability density of 2φ′(x - 2y) for (W1, M1).

The expectation of f(X1) for bounded measurable function f can be computed by integrating over this joint probability density.

The substitution z = y/2 – x was applied in the inner integral, and the order of integration switched. The probability density of X1 conditioned on W1 > 0 is therefore,

Conditioned on W1 < 0, we have already shown that the density is 4φ(2x) over x < 0 so, taking the average of these, we obtain

This is plotted in figure 3 below, agreeing with So’s numerical estimation from the Twitter post shown in figure 1 above.