Spitzer’s formula is a remarkable result giving the precise joint distribution of the maximum and terminal value of a random walk in terms of the marginal distributions of the process. I have already covered the use of the reflection principle to describe the maximum of Brownian motion, and the same technique can be used for simple symmetric random walks which have a step size of ±1. What is remarkable about Spitzer’s formula is that it applies to random walks with any step distribution.

We consider partial sums

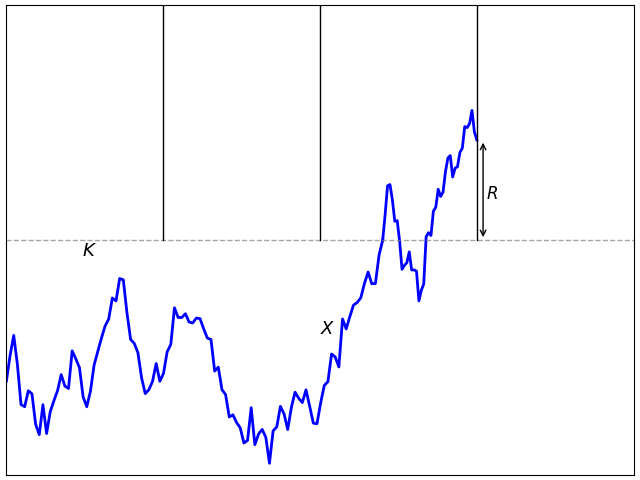

for an independent identically distributed (IID) sequence of real-valued random variables X1, X2, …. This ranges over index n = 0, 1, … starting at S0 = 0 and has running maximum

Spitzer’s theorem is typically stated in terms of characteristic functions, giving the distributions of (Rn, Sn) in terms of the distributions of the positive and negative parts, Sn+ and Sn–, of the random walk.

Theorem 1 (Spitzer) For α, β ∈ ℝ,

(1) where ϕn, wn are the characteristic functions

As characteristic functions are bounded by 1, the infinite sums in (1) converge for |t|< 1. However, convergence is not really necessary to interpret this formula, since both sides can be considered as formal power series in indeterminate t, with equality meaning that coefficients of powers of t are equated. Comparing powers of t gives

| (2) |

and so on.

Spitzer’s theorem in the form above describes the joint distribution of the nonnegative random variables (Rn, Rn - Sn) in terms of the nonnegative variables (Sn+, Sn–). While this does have a nice symmetry, it is often more convenient to look at the distribution of (Rn, Sn) in terms of (Sn+, Sn), which is achieved by replacing α with α + β and β with –β in (1). This gives a slightly different, but equivalent, version of the theorem.

Theorem 2 (Spitzer) For α, β ∈ ℝ,

(3) where ϕ̃n, w̃n are the characteristic functions

Taking β = 0 in either (1) or (3) gives the distribution of Rn in terms of Sn+,

| (4) |

I will give a proof of Spitzer’s theorem below. First, though, let’s look at some consequences, starting with the following strikingly simple result for the expected maximum of a random walk.

Corollary 3 For each n ≥ 0,

(5)

Proof: As Rn ≥ S1+ = X1+, if Xk+ have infinite mean then both sides of (5) are infinite. On the other hand, if Xk+ have finite mean then so do Sn+ and Rn. Using the fact that the derivative of the characteristic function of an integrable random variable at 0 is just i times its expected value, compute the derivative of (4) at α = 0,

Equating powers of t gives the result. ⬜

The expression for the distribution of Rn in terms of Sn+ might not be entirely intuitive at first glance. Sure, it describes the characteristic functions and, hence, determines the distribution. However, we can describe it more explicitly. As suggested by the evaluation of the first few terms in (2), each ϕn is a convex combination of products of the wn. As is well known, the characteristic function of the sum of random variables is equal to the product of their characteristic functions. Also, if we select a random variable at random from a finite set, then its characteristic function is a convex combination of those of the individual variables with coefficients corresponding to the probabilities in the random choice. So, (3) expresses the distribution of (Rn, Sn) as a random choice of sums of independent copies of (Sk+, Sk).

In fact, expressions such as (1,3) are common in many branches of maths, such as zeta functions associated with curves over finite fields. We have a power series which can be expressed in two different ways,

The left hand side is the generating function of the sequence an. The right hand side is a kind of zeta function associated with the sequence bn, and is sometimes referred to as the combinatorial zeta function. The logarithmic derivative gives Σnbntn-1, which is the generating function of bn+1. Continue reading “Spitzer’s Formula”